Introduction

Civil society organisations (CSOs) moved towards adopting increasingly professional working methods in the past decade. They now rely to large extent on mechanisms and tools similar to those of the private sector. However, the transition towards using such working methods requires completing tasks properly based on research, whether the task is to define and develop strategies and procedures, or identify tools and resources. Contrary to the private sector, CSOs work relies on volunteer-ing and public funds to serve society; therefore, a huge responsibility rests on the shoulders of people working in this sector, to ensure the best level possible of transparency, productivity and quality.

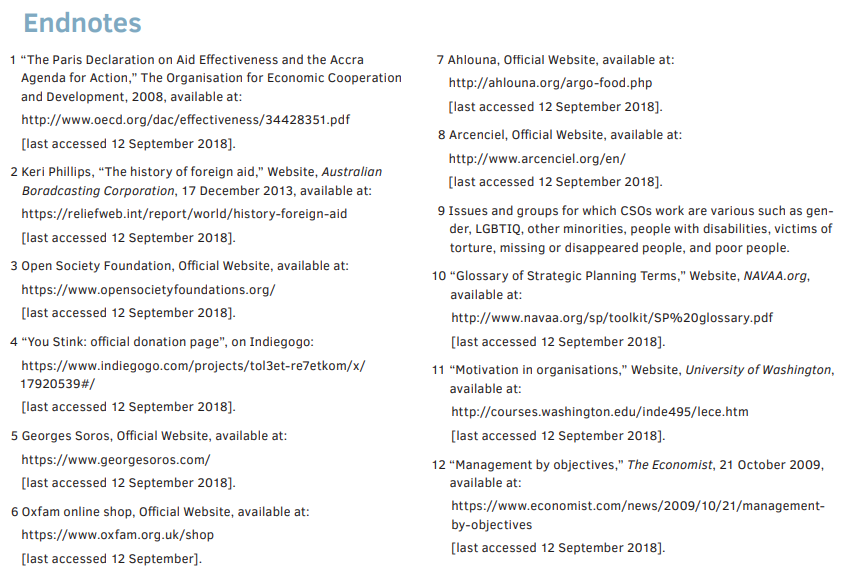

Donors from around the world consider that their interest in preserving social, cultural, political internal security is today a cross-border interest. Contagious diseases, for example, spread beyond borders, thus all donors be it states or organisations believe that international solidarity is nec-essary to defend the interests of citizens. For this purpose, they shifted the focus of their financial support towards specific sectors and regions around the world according to their interests and values, and perhaps the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness is a significant indicator of this shift.1

Since donors have the responsibility to defend the interests of taxpayers both locally and internationally, and considering the local civil society’s aim to ensure better transparency and effectiveness, donors and CSOs sought to build ties of cooperation between them. Therefore, it was nec-essary to sign agreements in order to work on achieving common goals based on agreements about their purpose, duration, and beneficiaries. Working procedures were improved and CSOs use it today to prepare calls for funds based on well-planned proposals. These calls for funds are prepared based on clearly defined writing methodologies and/or specific models. These models and proposal contents are today the most import-ant factors determining whether projects would receive funding.

This guide provides you with the tools needed to facilitate the proposal writing process and securing funds, by explaining the criteria upon which most donors base their decisions to provide funding, while taking into account the subtle differences between one donor and another.

This guide comprises two equally important sections:

- Understanding the funding world

- The stages of proposal writing

In the first section, we focus on defining the concept of funding grants, in addition to how to identify our funding needs, how to select funding partners for a said project, and how to target partners and persuade them of the proposed idea. In the second section, we present the phases needed to formulate a comprehensive proposal, and the main themes to tackle, the idea, objectives, and expected results formulation process, and finally how to develop financial budgets.

This guide seeks to help local CSOs answering the following questions: Does the organisation need funding? Is the required technical knowledge about transparent spending procedures available? To what extent is receiving this grant in agreement with the organisation’s values? How can we deal with differences between the values and objectives of the organisation and those of the donor? And, finally, how can we ensure the sustainability and continuity of work in the event of end or interruption of funding? Ensuring sustainability and effectiveness of funds is one of the major elements of accountability when selecting grants. Being a member of the civil society community means that these questions are necessary to ensure your organisation’s work values, its sustainability, and abidance by the goals for which your organisation was established.

I. Understanding the funding world

1.1Studying donors

Funding is and has always been part of the existence of civil society. It was certainly less organised than it is today. The concept of foreign grants and funding to developing countries emerged in the 19th century.

2

CSOs only need to realise that the need for funding is not the goal in itself, but rather a means to achieve the objectives of their organisations.

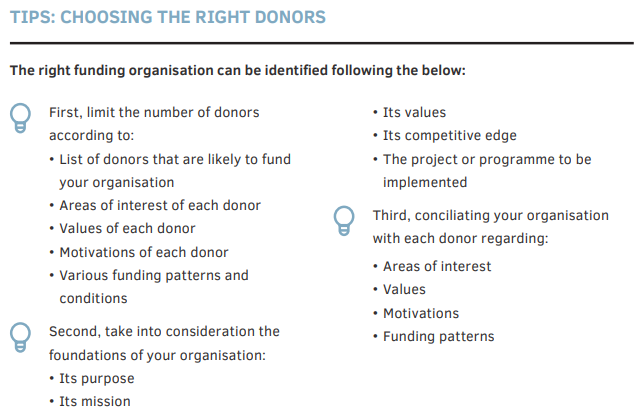

When organisations seek funding from donors, they should dedicate more time for preparation and planning in order to increase chances of successfully receiving the required resources, as submitting a proposal without proper research or sending a request for funds to donors based on speculation are no longer deemed efficient ways to secure. In fact, organisations should first focus on identifying what suits them and their objectives, in addition to identifying what suits funding organisations.

Although non-governmental organisations are not-for-profit, implementing many of their activities and ensuring their continuity is not possible without funding. Sufficient resources should be available to cover the expenses, provide services, and help ensure sustainability. It is not recommended to initiate efforts to ensure funding by requesting it from a donor. To successfully receive funding 80% of the efforts should be made on planning and preparation, and the remain-ing 20% should be put towards the request.

Prior to initiating the process of planning and prepara-tion of proposals for programmes and activities requir-ing funding, your organisation should first proceed to seek information about the donors through research work to ensure receiving funds. The main steps required to prepare such research are set out below.

1.1.1Exploring funding sources

Individuals: Through donations, grants, and funds provided by individuals from the community, friends of the organisation, or supporters of an issue on which an organisation focuses. Such donations, grants, and funds are either paid in cash to the organisation or through money transfers; either in kind (direct dona-tions of equipment, materials, or other) or through modern communication platforms such as crowdfund-ing platforms.

Governmental bodies: CSOs cannot rely on govern-mental bodies in Lebanon for funding. Certain local organisations, charities, and healthcare associations, however, do receive annual funds from relevant min-istries for implementing projects in the regions where they operate. Nevertheless, CSOs around the world rely on funds provided by their governments and donations of individual members of their communities, including organisations working on advocacy and lobbying.

Institutions established by individuals or corporations: It is a common model on the international level. The Open Society Foundation,

3 George Soros

4 is one example of such institutions that often fund CSOs projects.

International Organisations and Agencies: These organisations receive funds either from their gov-ernments or from other funding sources, namely the private sector. They operate in countries that fall within the scope of their interest and the interest of their donors through local CSOs. With best practices in mind, local CSOs should consider whether they are interested in receiving such funds in the event their priorities and strategic plans are not in line with the plans and priorities of donors and funders.

Corporations: Many corporations seek to fund chari-table or development projects in order to polish their image before the public, given the nature of their operations or to lower their taxes. On the other hand, some private sector corporations truly believe that they should bear part of the responsibility by targeting pressing social issues, based on the concept of “Corporate Social Responsibility”.

Self-funded projects: Organisations can develop a business model to generate revenue that would be used to serve the goals of the organisation. International examples of such models include Oxfam’s online shop,

5 and local examples include Ahlouna association in Saida (production factory)

6 and Arcenciel

7 association. Such ideas and innovations contribute significantly to, first, ensuring financial stability and the organisation’s self-sustainability, and second, funding activities not covered by foreign grants.

8

1.1.2 Researching donors’ areas of interest

You can identify the areas of interest of funding organisations through reading their newsletters and brochures, and visiting their websites or social media pages. It is important to read carefully in order to identify whether the purpose, mission, and activities of the organisation are compatible with the areas of interest of the donor. The areas of interest of donor organisations can be summed up in three main areas of interest:

• Areas related to human rights issues: Women, youth, children, elderly, and refugees issues;9

• Areas related to geographical regions: a particular country or region;

• Concern about a particular type of issues, such as poverty, displacement, unemployment, disability, gender, labour rights, education, political participation, GBV, and others.

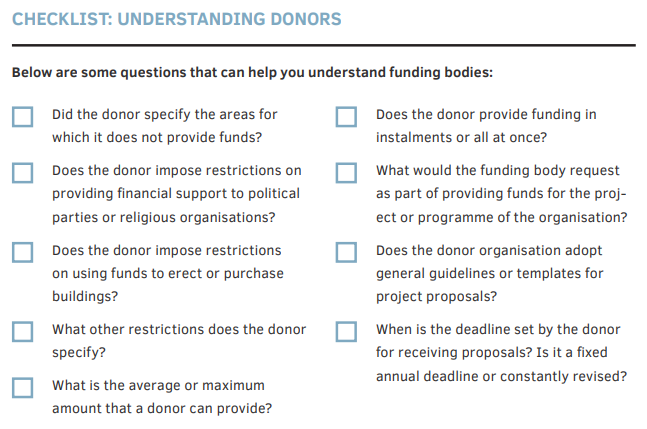

Funding is a delicate matter, each donor having its own priorities and areas of interest. Therefore, you should not submit proposals that do not fit in the donor organ-isation’s scope of interest, to avoid having it ignored. Keep in mind that funders’ priorities constantly vary due to changing circumstances and developments on the international and regional political scene, or due to strategic causes. For example, issues of displacement, protection, and countering terrorism are today among the major areas of interest of funding organisations.

1.1.3 Identifying donors’ values

Values are the group of ideas that help elucidate the beliefs and guiding principles of the organisation.10 Each organisation adopts its own set of values and beliefs. Therefore, it is important to research potential donors and identify their values while looking for fund-ing sources. Upon identifying resources and examining the areas of interest of each donor, it is also important to study documents issued by donor organisations to assess the values driving them. Being aware of their values can save you a lot of time and effort and help you determine the extent to which your organisation is compatible with the donor, and the probability of successful future cooperations.

1.1.4 Understanding donors’ motivations

A motivation is a set of drivers that make organisa-tions choose to adopt certain behaviours and not any of the other available alternatives.

11 To ensure securing funds, it is important to identify what drives donor organisations to provide funding, in addition to obstacles limiting that (for example, not approving of the nature of work of applicants, concerns regarding misuse of funds, or challenges relevant to the political, cultural, and social context). A thorough understanding of the motivations that determine donors’ decisions to approve funding requests gives you more chances to ensure successful application. This methodology allows consolidating the relationship of the organisation with donors and makes it easier to manage such a relation-ship. When the organisation’s motivations converge with those of a donor organisation it applied for funding from, it can contribute towards increasing the chances of approval of the funding request. Individual and insti-tutional donors can have various motivations, including:

Concern: Concern for certain issues, such as the environment, refugees, or violence against children for example, can constitute a motivation to provide support through granting funds.

Duty: Enjoying relative safety and social well-being as a result of having shelter, employment, good income, can drive some people to feel a sense of responsibility towards those lacking such opportunities, and cause an urge to support and help them. Religious and human values reinforcing this type of motivation, it is quite common among religious institutions and charities.

Personal Experience: Commitment to certain issues can sometimes be due to personal experience that motivates us to commit to helping our community or working on a particular issue. For instance, when a person or a family member suffers from a disease, we might develop a strong motivation to provide financial assistance to an organisation working on fighting such disease.

Personal Benefit: Some individual or institutional donors provide funding in view of achieving personal interest, such as building a personal relationship with an important public figure, or mentioning the name of a certain organisation to gain more credibility.

Taxes: Although taxes are not among the main motiva-tions for granting funds in Lebanon, tax exemptions and cuts may be one of the factors that encourage individ-uals and international institutions to provide funds and donations.

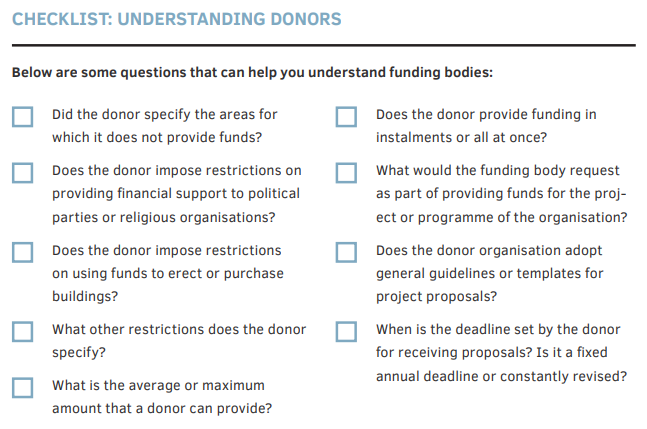

1.1.5 Understanding funding patterns and conditions

Researching funding patterns and conditions is the final phase of this process. This helps in identifying the funding organisations that are more likely to embark in partnerships and provide funding. It should include studying the nature and amount of funds previously provided, the project and programme areas, funding patterns, geographical distribution, and other factors. It also helps reveal the type of support provided, as it can encompass financial support in the form of dona-tions, logistical support, or in-kind support through providing specialised training in different areas, for example. Undertaking this study helps organisations avoid conflicting with donors’ terms and regulations.

1.2 Improved targeting of donors

Below are the procedural steps to take studying donors. These steps help in reaching better funding bodies for your organisation, and transforming potential donors into actual ones.

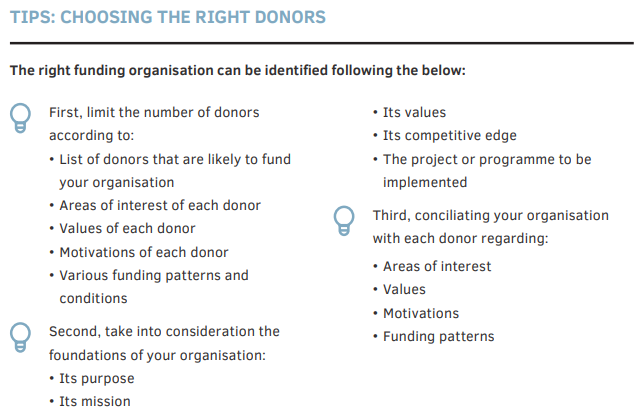

1.2.1 Selecting the best fund

In order to save time and effort when fundraising, it is important to review the list of potential donors then select the ones that are the best fit for you, to focus exerted efforts on them. This might mean disregarding donors that are less likely to provide funding, and thus focus on other partners.

1.2.2 Preparing the grounds

Inquiring about the process of requesting funds is similar to harvesting land. The preparation process, whether in agriculture or fundraising, requires plough-ing the land then seeding. This means that you cannot start by requesting a certain amount of funding. You rather start with attracting donors and paving the way for them to become interested in the organisation and familiar with it. Indeed, decisions to grant funds to an organisation are based on what donors already know about its work and activities. If funding organisations are not familiar with the work of the organisation, or if they hear information or watch news that negatively depict it, they would refrain from granting funds or supporting it, no matter how noble its objectives are. The main methods used to introduce donors to your organisation are:

• Periodic publications: Pamphlets, newsletters, websites, and social media pages. These introduce people in general, and donors in particular, to the work of the organisation. Therefore, it is important to ensure their design is innovative so that the organisation leaves a good impression.

• Presentation about the organisation’s activities and programmes: Prepare a presentation about the organisation’s activities and programmes, along with pictures and brief descriptions when needed.

• Seeking advice: Seeking technical advice from a funding organisation regarding a specific project would give the donor the opportunity to learn about the activities of the organisation and its expertise in project or programme management.

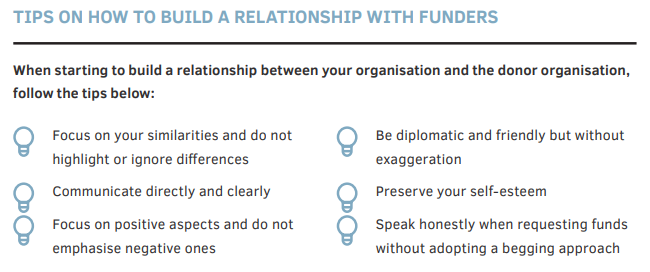

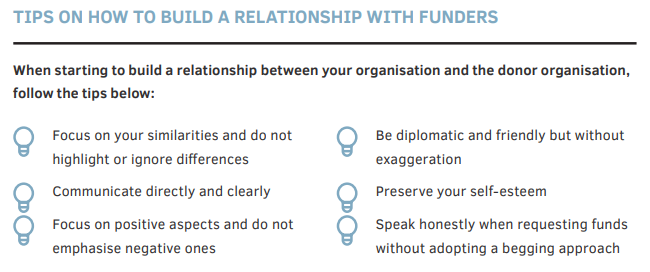

1.2.3 Building personal relationships with funding organisations

Building personal relationships with donors consists of working towards ensuring a sense of harmony and familiarity, and finding compatible and similar interests between both organisations. Any communication with donors should be considered a way to build stronger relationships with them, and improve your understand-ing of what drives them to provide funding or enhance their engagement in your activities. Therefore, you should be well aware of the level of participation the donors seek. Sometimes, contacting certain donors when needing further support to fill funding gaps is sufficient. Some other times, some donors require receiving the organisation’s newsletter regularly, or receiving letters or reports highlighting the progress achieved in the funded project. While other funding bodies require receiving invitations to attend or participate in the organisation’s fundraising events.

1.3 Emphasising your organisation’s strengths

In this section, the organisation should present its his-tory and achievements, in addition to its institutional capabilities, current and previous partners, as well as the amount of funds received and names of previous and current donors.

Building your case:

If you expect certain individual or institutional donors to fund the organisation, it is important to be able to provide good justifications that encourage those to provide their support to the organisation. Therefore, it is important to present the cause of the organisation and its relevance in order to convince them to provide support. When presenting your organisational capacities and strengths, it is important to include the organisation’s description, purpose and experience in managing previous projects and programmes, as well as the organisation’s capability and resources for implementing the project or programme in terms of management, human resources, finance, and technical skills. Therefore, it is important to highlight these capabilities to persuade donors of the feasibility of the project or programme and its successful implementation.

Moreover, the organisation’s assessment of capacities should highlight its management style, its assessment methodology, its ability to avoid obstacles that could potentially be faced when implementing the programme or project, as well as highlighting the issue or need the organisation intends to address and for which it requests funds. Additionally, include the project or programme beneficiaries, the organisation’s level of commitment towards them and how it addresses issues they face, and the improvements in the community that would occur as a result of this project.

Stating the capacities of the organisation aims to convince donors of the issue at hand, persuade them that the organisation is able to address this issue consid-ering its strengths and financial and human resources, present the rationale for providing funds, and explain how the requested funds will be spent and to which end.

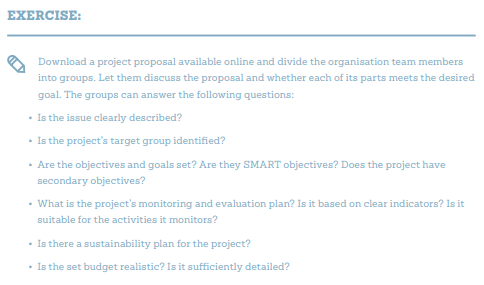

II The stages of proposal writing

2.1 How to start writing a proposal?

It is important to determine a number of components that might seem nominal, but in reality, they are crucial to successfully writing a comprehensive proposal. One of the most important elements is to appoint a coor-dinator for writing the proposal who would be respon-sible for gathering the proposal’s different parts and combining them based, either, on the template provided by the donor, or on a defined and scientific method-ology. The second factor that should be considered is determining whether the idea of the project emerged due to a need identified by the organisation and con-sidered part of its strategy, or resulted from a donor’s “call for proposals” which converges with the priorities of the organisation. After that, the organisation should discuss internally whether it is appropriate to answer this call or not.

Usually, organisations set a baseline for their first project activity, which would require subsequently rearranging the project based on its results. Setting the baseline while writing the proposal is an indication of the organisation’s professionalism and a strong proposal.

Developing the project should be organised according to the timeline provided by the donor, as most funding organisations impose a final deadline for proposals submission. Therefore, it is important to coordinate efforts and manage your time throughout the different phases of proposal writing, keeping in mind that it is commonplace to prepare and finalise a proposal within a few days before the submission deadline.

Organisations believe that submitting proposals as part of a coalition grants them a better chance to receive funding. Donors do, usually, encourage joining efforts through CSOs coalitions, provided these coalitions comprise various stakeholders with complementing efforts and areas of expertise in view of achieving better results. However, the problem lies in the lack of a clear or well-developed common vision needed to ensure successful implementation of joint projects, and is not only characteristic of the Lebanese local context, but also applies to other countries. In this vein, it is considered best practice to determine the roles, frame-works for implementation, coordination, and reporting in the first phase of building the coalition while writing the funding proposal, and not delay it.

2.1.1 Useful terms

Prior to providing descriptions for the different proposal writing phases, and to make the proposal writing process easier, the organisation should be aware of a number of terms usually mentioned in donors’ calls for proposals.

2.2 Preparation phase

Proposal writing beginners believe that filling the required template is an essential step in order to receive funds faster; however, the preparation phase helps make the process more time efficient. Reviewing available literature makes the proposal writing process easier, and adding references and updated information gives it more credibility. Therefore, you should rely on various sources (organisation’s library, online resources, public libraries and other sources) then review them in preparation for the subsequent phases:

• Literature review

• Identification and analysis of needs

• Field research

• Learning about the available services provided by other institutions

• Identifying relevant funding sources, their proposal’s basics and requirements, and initial assessment of funding strategy.

• Review of organisational capacities, objectives, and human resources according to the project idea.

• Setting an action plan to develop the project, identi-fying target groups and determining stakeholders and actors to be involved in its process.

• Documents and resources owned by the organisation

• Similar projects previously submitted by the organisation, whether they were successful in fundraising for or not.

• A list of donors with which the organisation worked in the past

• Developing a comprehensive file about the organisation including its name, history, objectives, strategy…)

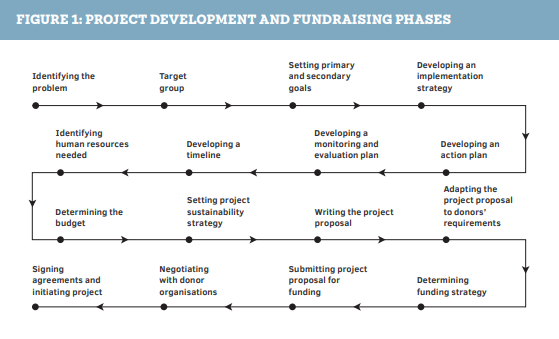

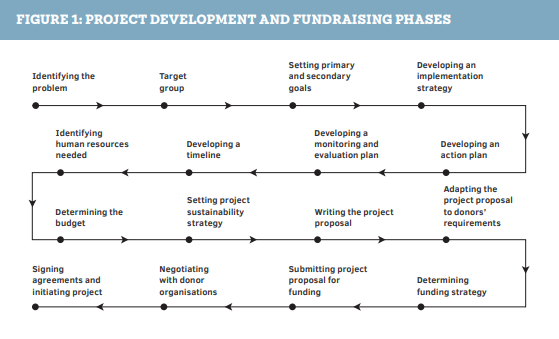

Upon completion of the preparation phase, you can go forth with the following phases that include proj-ect development, writing and finalising the proposal for submission, and finally signing the partnership agreement with the donor organisation, then initiating project implementation. (See figure 1).

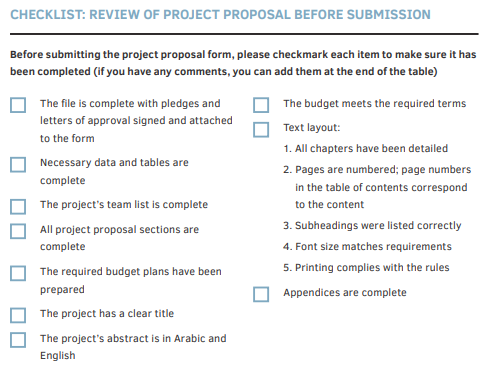

2.3 The project proposal template

Funding bodies have specific requirements and templates to follow for proposal approval. Therefore, the organisation should be aware of these requirements prior to submitting the proposal and abide by them when developing its project, budget, and any other ele-ment mentioned in the donor’s call. Below are the main components, often found in a project proposal template, as well as a detailed description of each:

• Letter of approval: The letter of approval is a document that indicates to the donor the organisation’s work commitments, briefly stating its request. It often refers to any previous meetings held between the funding organisation and the organisation, and is signed by authorised individuals.

• Cover: The cover features the proposal submission date, the project name (in which project content is highlighted), the name of the organisation applying for funding, the contact person, and the organisation’s address. To make it more eye-catching, you can add a picture relevant to the project for example.

• Summary: Brief presentation of the issue addressed by the project, with background information, the objectives of the project, an overview of action plan and activities. It also includes the requested funding amount, in addition to information about the organisa-tion’s capacities and strengths in leading the project. The summary should be comprehensive while remaining concise, and able to draw the attention of readers.

• Introduction: Provides information about the organisa-tion requesting funding, its legal status, and its ability to manage the project. It highlights the organisation’s achievements and credentials relevant to the specified field. It also explains the proposed project’ relevance to the objectives of the organisation, mentioning previously funded projects, especially successful ones that have received positive feedback. Finally, it provides a brief description of the issue addressed and target objectives, in order to highlight the significance and relevance of the project to the donor.

• Issue/Need: Features an accurate and comprehensive description of the issue (backed by information and indicators about its spread), an analysis of its causes, and effects, and the importance of addressing it.

• Target group: This section describes the target group and the ways in which they are affected by the issue or problem addressed in the project. It specifies the geographical scope of the project, and analyses the relationship between the target group and other groups and communities around it.

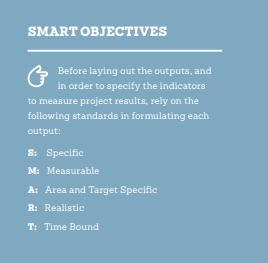

• Objectives and strategies: This section presents the overall objectives of the project, the main and sec-ondary objectives, and a description of the approach adopted (strategy).

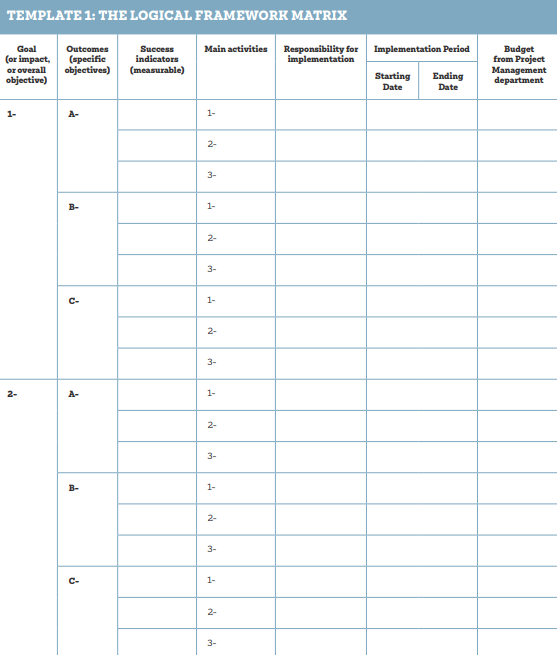

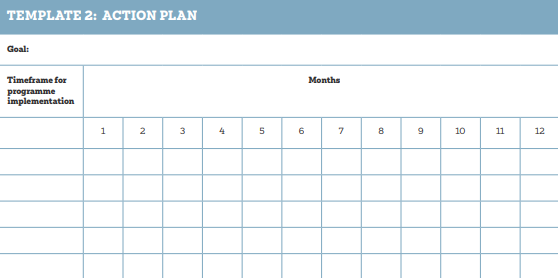

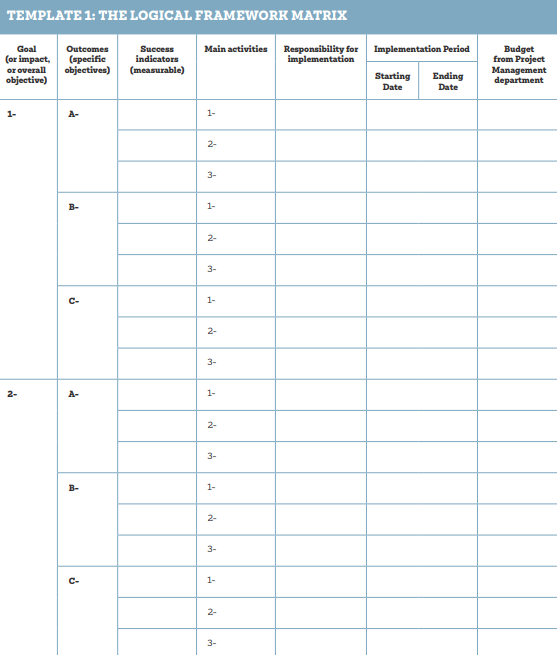

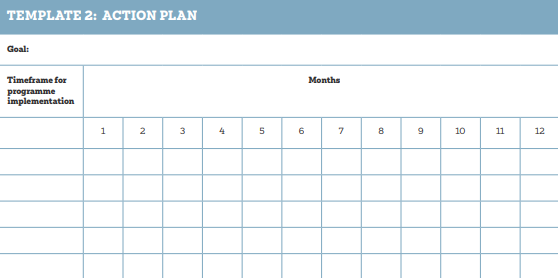

• Approach and activities: This section describes the project’s activities that will serve to the stated objectives, in addition to the action plan and numbers targeted (See Template 1).

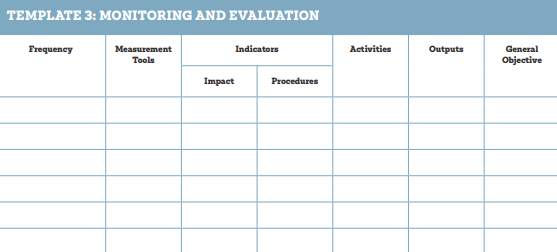

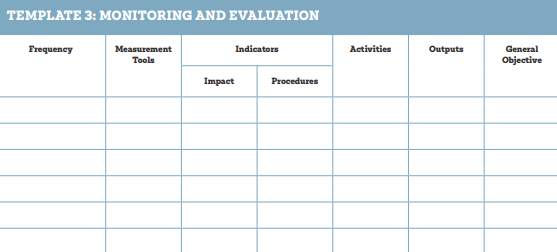

• Monitoring and evaluation plan: Provides an overview of the monitoring plan the elements used to evaluate progress and develop indicators, and the type of evaluation plan, whether it is internal or external, etc.

(See Template 3)

• Sustainability plan: This section describes the organi-sation’s project needs in terms of human and financial resources, and sets a plan for the sustainment of the project ensuring its longevity, from a financial and management perspective.

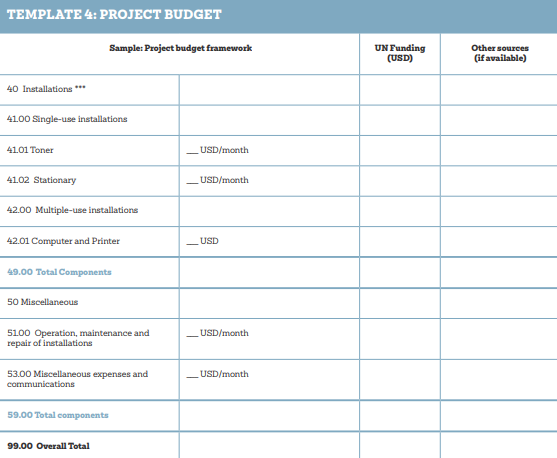

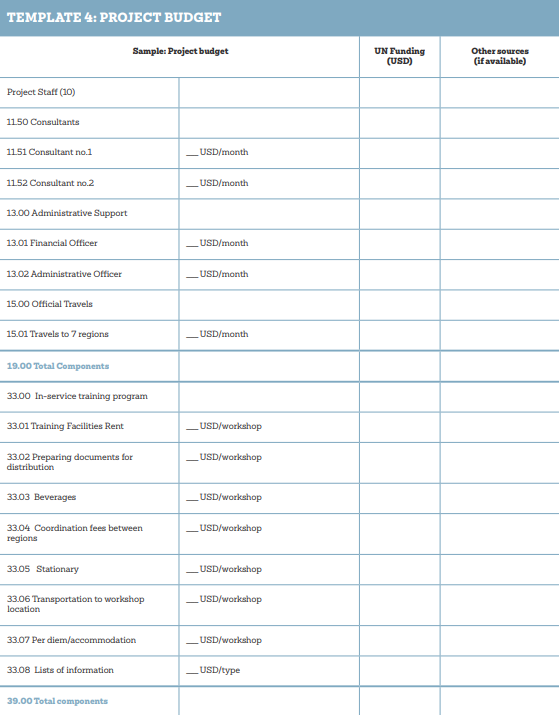

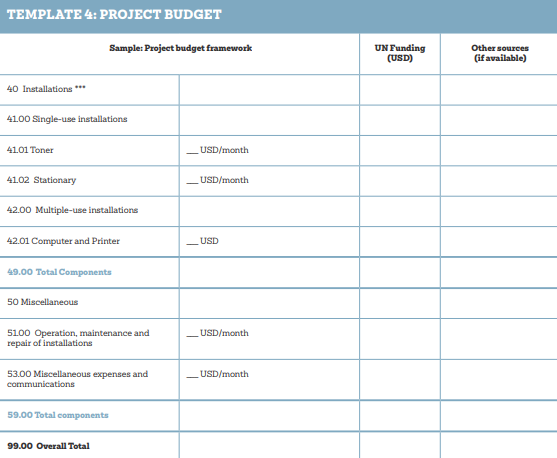

• Budget: This section provides a summary of requested funds according to set budget lines, in addition to a description of some expenses, and financial statements describing the expected expenses in detail according to budget items.

• Annexes: Annexes can include several documents rele-vant to the project, however, make sure these annexes are useful and provide required clarifications, and refer to them in the body of the proposal when needed. Annexes may include: a brochure about the organisa-tion, annual and financial reports, the detailed project budget, detailed action plan, pictures of activities from ongoing programmes relevant to the project proposed, additional plans related to the project (such as the funding plan, other partners), endorsement letters from partners, curricula vitae of main positions candi-dates, and any information or publications supporting the proposal.

In the following section, some of these main com-ponents are detailed, particularly those for which requirements differ from one donor to the other.

2.3.1 Problem analysis

Formulating the problem in a clear, accurate and com-prehensive manner helps you identify the focus of the project, avoiding surface-level symptoms and focusing on addressing significant elements. To properly formu-late and present the issue or problem addressed, you should provide a description of the issue, its causes, and implications as follows:

Problem Description

• Accurate assessment of the circumstances that need changing

• The group affected by the issue and how it impacts them

• Quantitative description of the issue and its spread

• Elements relevant to organisational needs

• Stakeholders concerned by the issue and how they address it

Causes

• Root cause of the issue

• Factors causing the issue

• The inter-relation between causing factors

Implications

• Impacts of the issue

• Groups affected by these implications and how they are affected.

• These implications’ impact on social, political and economic contexts

• Reasons to address the issue (justification)

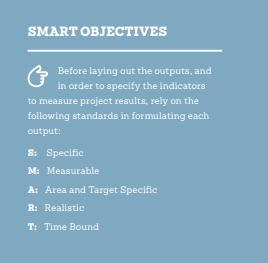

2.3.2 Goals, objectives, and activities

First:

The main objective or goal: The main objective describes the expected situation upon the end of project implementation, which represents a solution to the previously identified problem, and determines the project’s scope of work (please see Template 1).

Second:

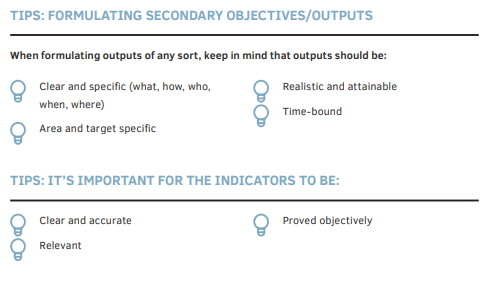

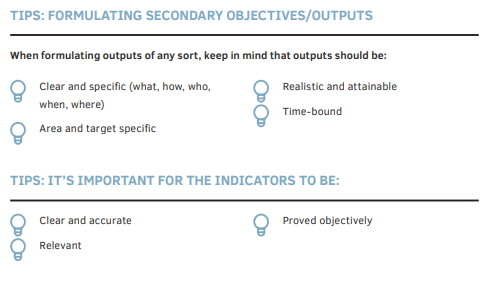

Secondary objectives or outcomes: A series of specific achievements required to fulfil the main objective. Clearly formulating secondary objectives improves activity planning (please see Template 1). There are two types of secondary objectives:

Qualitative secondary objectives: These are specific objectives aiming to implement a practical activity with no expected results. There are two types of specific objectives:

A. Objectives that define action and how to implement it. Terms used to formulate these objectives include: improving, helping, enabling, coordinating, promot-ing, and strengthening. Usually, it is recommended to avoid these objectives, as they are not specific and difficult to measure, and are mostly used to describe strategies rather than achievements. It is recommended to use them in case the procedure is important to the development of the project or programme, of if it’s a donor requirement.

Example: Improving the quality of elementary school training next year; coordinating action of institutions working on women economic rights.

B. Specific objectives that describe the type of action or activity. Terms used to formulate these objectives include: training, establishing, creating, developing, and organising. This type of objectives is widely used and helps stakeholders to manage, monitor and evaluate the project. However, these objectives do not specify the impact of activities on individuals.

Example: Training 50 elementary school teachers on using the learning through drawing method.

Secondary objectives with final output: These

objectives describe the impact of the project on the target group. Terms used to formulate these objectives include: increase and decrease. This type of objectives is oftentimes similar to the main objective, so it is necessary, when developing main and secondary objec-tives, to ensure they are all connected to each other and stemming from the identified problem, in order to achieve the project’s overall objective.

Example: Improving the standard of living of 200 marginalised families in Northern Bekaa during 2019

Third:

Activities: Interventions and direct actions led by the project and that are in accordance with the outputs. All in all, these activities would, in theory, lead to achieving the goals set beforehand.

Example: if the goal is to train 50 primary school teach-ers on how to include drawing as a teaching method, the activity or intervention of the project would be to schedule three workshops for teachers, on different dates before the start of the next academic year for instance, introducing and training them on drawing as a teaching method.

2.3.2 Monitoring and Evaluation: Spot the differences

Monitoring

A periodic process that aims at gathering information regarding different aspects of the project. Monitoring provides project stakeholders with the necessary information (see template 3) for:

• Analysing challenges and addressing them

• Maintaining activities within the set timeframe

• Measuring progress towards achieving goals, formulat-ing and/or reviewing future goals.

• Taking decisions concerning human, financial, and physical resources.

Evaluation

Evaluation consists of the process of information gathering and analysis to determine whether a) the project is achieving the activities planned, b) the extent to which the required goals are being accomplished through these activities. Evaluation is done periodically or at the middle or end of the project (see template 3).

Elements of Evaluation:

• The extent to which the action plan is implemented

• Development of rules and regulations

• Implementation of activities planned and the extent to which goals are being achieved

• Project results

• Accurate and efficient financial management for the project

The main difference between the two:

• Timing

• Focus

• The extent of details examined

2.3.4 Indicators

Indicators are quantitative and qualitative success criteria enabling the project stakeholders to evaluate the achievement of the project goals. Some of the indicators used are:

A. Output indicators: indicators describing the project outputs, such as the number of people trained within the project.

B. Result indicators: indicators measuring concrete change that results of the project or the activity, such as a decrease in infant mortality rate; number of women finding employment, etc.

2.4 Logframe

In addition to the project’s purpose, goals, inputs and outputs, and quantitative and qualitative indicators defined, many funding organisations rely on a template annexed to the proposal, called logframe matrix, which organises these elements in a systematic way for a bet-ter understanding of the expected inputs and results.

Most templates of the kind have clearly defined fields that need to be filled with the right information as taken from the project proposal, without needing to further elaborate it. Since its adoption in 1954,

12 management by objectives was and remains the com-mon approach used by many organisations, whereby projects are carried out and evaluated based on the objectives it defined.

With the concept of development projects evolving, global debates on the impact and achievements of such projects started, and we have witnessed, over the past two decades, a gradual transition towards a different way of thinking based on management by results. The latter has, until now, proven to be efficient in ensuring a better planning and evaluation of projects.

Nowadays, the United Nations system, the European Union, multilateral development agencies, international human rights organisations, and humanitarian organ-isations, have all worked on encouraging their local partners to adopt the result-oriented planning, i.e. the logframe method, when organising, implementing, and evaluating projects and programmes (see template 1).

The logframe allows different stakeholders at all stages of the project – from the planning (proposal writing stage to the evaluation stage – to grasp the situation and implement sound procedures, based on four indicators:

Adequacy: the extent to which the project is in line with the basic needs of the targeted groups and areas, that have been defined in the problem analysis.

Impact: whether the proposed activities would achieve expected results.

Sustainability: the extent to which the proposed activities would impact the targeted areas and lives of the target groups on the long run.

Cost efficiency: whether the necessary funds or those disbursed on the project are realistic compared to the results.

Please keep in mind that all templates in this module are only indicative, acting as mere examples, as many donors have their own forms.

2.5 Project longevity and sustainability

The project’s continuity and sustainability reflect its ability to persist and be self-sustained by its own resources (human, physical, and financial), despite the lack of external support. The sustainability plan is one of the biggest challenges facing funded projects, as it is diffcult to guarantee it, and organisations might even find it burdensome acquiring the equipment and abilities needed to ensure continuity. This is due to either miscalculation or the lack of expertise.

There are three levels of continuity: a) financial, b) institutional (or programme continuity), and c) political. Some strategies applied to ensure continuity on said levels are as follows:

A. Financial sustainability

• Establishing an internal system to cover project expenses, like an income-generating model

• Seeking more than one donor, locally or internationally

• Initiating other income-generating projects to cover the activity’s expenses

• Receiving in-kind support from other institutions and forming a network for joint efforts.

• Providing other institutions with technical assistance to gain support

• Relying on in-kind support, e.g. the local community securing a centre for hosting activities

B. Institutional or programme sustainability

• Developing the organisation’s vision, message, and values

• Developing technical expertise among employees

• Setting a system for regular performance assessment

• Providing a flexible response to the changes in internal and external environments

C. “Political” sustainability

• Receiving governmental support for the project and the institution

• Receiving support from members of the local commu-nity and engaging them in the project

• Supporting long-term policies

• Developing cooperation networks with other institutions

• Forming pressure groups in collaboration with other organisations

• Holding awareness-raising meetings and reaching out to the press to publish the project’s activities and results.

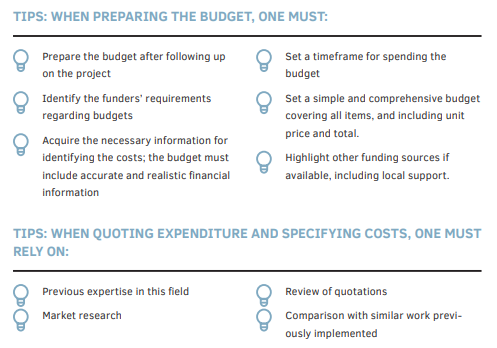

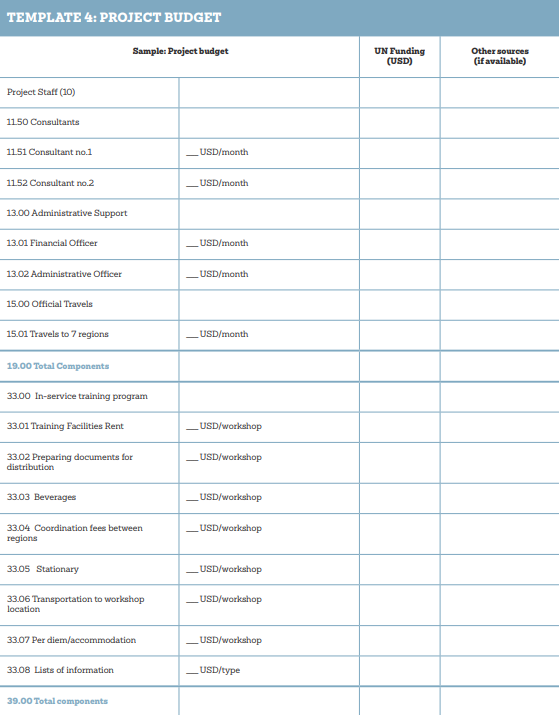

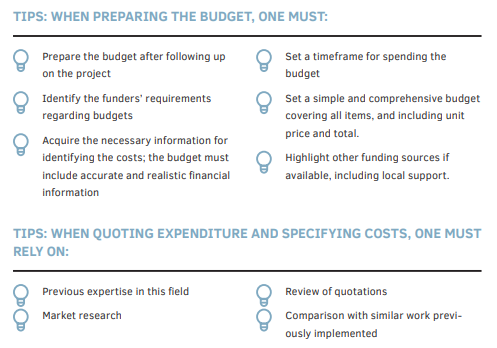

2.6 Budget

Calculating all of the project’s direct (activities) and indirect (administrative costs) financial costs in an accurate and organised way.

Budget

A financial plan based on projections and anticipation, but involves at the same time calculated figures based on a serious study and adopting internal policies that help calculating figures accurately, e.g. determining salaries and wages according to the salary scale of the organisation (see Template 4)

Balance

The institution’s or association’s financial status at a given time, which reflects the expenses compared to the project’s financial planning, in compliance with the items agreed upon, and the suitability of the figures.

The budget aims at:

• Ensuring the availability of resources needed to reach the goals as designed in the proposal

• Specifying the project’s implementation cost

• Ensuring the efficient use of the limited resources available

• Providing a follow-up tool to compare between the real cost and the estimated cost.

The project proposal budget includes a systematic mathematical formula involving some of the main items such as: (see template 4)

• Human resources

• Equipment and materials

• Transportation and travel costs

• Programme costs

• Other expenses

These items can be summed up as follows:

A. Investment Costs: the expenses paid for purchasing buildings and property or heavy equipment that can serve for more than one year or cycle.

Example: in order to organise the vocational training project, a suitable space (building) must be provided; in case of purchasing, these purchasing costs cannot be included in a one-year budget, but rather the annual depreciation of said building must be added to the budget and divided by the number of cycles.

B. Operating costs: the expenses paid for the purchase and maintenance of equipment, and materials to be entirely exhausted by the end of the financial cycle.

Example: in order to organise the vocational training project, catering and stationary should be provided for hosting the training. These materials count as operating costs ending by the end of the project’s financial year and the activity itself.

Closing remarks

This guide aims at providing tools for identifying funding sources and giving practical insights and tips regarding the main steps of writing a project proposal. It also indicates what needs to be taken into account when developing projects and attempting to screure funds for them.

Still, a few issues, that are overlooked in the sector, should be taken into account. Most practitioners in project development make a common mistake linked to self-evident assumptions, when they assume that whoever is reading the project proposal is familiar with the context, timeframe, or geographic framework of the issue at hand. However, the donor might not be fully aware of such details. As such the organisation’s political, social, cultural and geographical contexts and the nature of its work must be explicited, in addition to clearly identifying the target groups.

The organisation team members often dedicate a long time for putting together an integral vision for the project proposal, taking into account all adopted criteria and accurately addressing issues while setting a sound strategy for work. If, eventually, the donor rejects the proposal and partners with another organisation, one shouldn’t be overcome by despair, as this is ordinary and common.

Note that some CSOs fall into the trap of trying to match their proposals to the donor organisation’s objectives and strategies, creating justifica-tions to receive funding at the expense of their own principles and values. Funding must not constitute a goal in and of itself, but rather be thought of as a means to put in place projects that respond to needs on the ground, and sustaining the organisation.