This Conflict Analysis Digest is composed of:

I. Current conflict trends

1- Overview of mapped mapped conflict incidents in Lebanon between July 2014 and March 2015

2- Mapped air space violations and other incidents classified as Border conflict (at the Israeli border) between July 2014 and March 2015, with a focus on the surge in tensions on the Israeli border during the last week of January 2015

3- Mapped air strikes, clashes/armed conflicts and violations classified as Syrian Border Conflicts

4- Ratio of “power and governance conflicts” and “individual acts of violence” mapped between July 2014 and March 2015

II. Brief thematic report

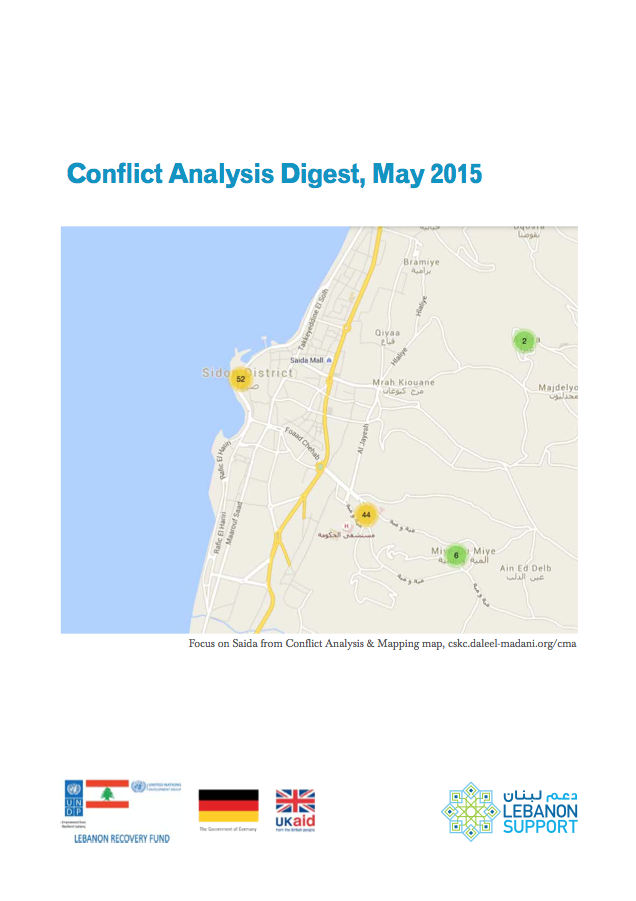

Spatial Fragmentation and rise in poverty: the conflict context in Saida

Abstract:This short report provides a contextual and analytical summary of the conflict in the region of Saida, south of Lebanon, with a focus on spatial struggles and poverty growth. It describes the main conflict actors and how they have historically contributed to the shaping of conflictual dynamics in Saida from the fifties until today. Findings highlight that while most observers and media attention are focusing on the “radical Islamist danger,” stakeholders and social actors in the city perceive the most pressing threats to be notably related to social factors, including the density of the population, spatial frag- mentation, and rise in poverty.

I.Current conflict trends

1- Overview of mapped conflict incidents in Lebanon between July 2014 and March 2015

The above graph represents the fluctuation of conflict incidents that were reported andmapped between July 2014 and March 2015. The typology above, used to classify security incidents, stems from the analysis of existing incidents, and was developed in the early stages of the project. This graph provides an overview of the mapped incidents since the beginning of data collection, and reveals that conflicts of social discrimination and of socioeconomic development were the least reported on, hence the least mapped, in comparison to conflicts of other nature that were more thoroughly tracked by media, NGO reports, and first-hand accounts. This is a shortcoming that should to be taken into account when considering the Conflict Map. The mapped social discrimination conflicts mostly include curfews enforced by localities, as well as state actions against vulnerable populations, such as arrests and deportations. Also included were collective actions such as protests or solidarity sit-ins. On the other hand, the mapped socioeconomic development conflicts consist mostly of collective actions, like the EDL workers mobilisation.

2- Mapped air space violations and other incidents classified as Border conflict (at the Israeli border) between July 2014 and March 2015, with a focus on the surge in tensions on the Israeli border during the last week of January 2015

The ongoing high frequency of Israeli violations of Lebanese airspace has almost become a habitual Israeli breach of Lebanese sovereignty. However, within this pattern, specific phases of tensions can be noticeable; the above graphs record a visible tension in January2015 that stemmed from sporadic confrontations between the Israeli Armed Forces and Hezbollah,—more specifically the Quneitra Martyr’s branch, which emerged following attacks on Hezbollah and its allies in Syria. The heightened level of tension was also visible over the last week of January 2015 through the use of heavy artillery and bombardments on both sides of the border, in addition to armed clashes. This tension concorded with a buildup for the March 2015 Parliamentary elections in Israel, which might give some insight into the understanding of the increasingly belligerent stance adopted.

3- Mapped air strikes, clashes/armed conflicts and violations classified as Syrian Border Conflicts.

The period between July 2014 and March 2015 witnessed an ongoing and increasing number of incidents, ranging from sovereignty violations (airspace and land violations, and border crossings) to belligerent actions (air strikes and clashes/armed conflicts). In terms of breaches of sovereignty, infiltration attempts seem to have evolved from aerial to territorial. While this corroborates the porosity and vulnerability of Lebanese borders, it is also an indicator of security breaches, an issue to be tackled and confronted by Lebanese authorities.

4- Ratio of “power and governance conflicts” and “individual acts of violence” mapped between July 2014 and March 2015

II-Brief thematic report

Saida: a contextual matrix

Saida’s demographic landscape is shaped by major local and regional happenings. The settlement of first generation Palestinian refugees in the city 70 years ago; the rise of the influence of Fatah over it forty years ago; the three-year-long Israeli invasion of the city thirty years ago; and the neighboring civil war in Syria have all contributed to the city’s unique makeup. Saida today is an agglomeration of nearly 260,000 inhabitants,1 two-thirds of which are refugees or descendants of refugees that have been displaced from either Palestine or Syria.

In these circumstances, the city’s local social scene is characterised to a great extent by a mix between Lebanese and Palestinians. For instance, it is estimated that more than 60% of the families living in Saida are of Palestinian or mixed (Lebanese-Palestinian) origin.2 The two refugee camps South East of the city on the first slopes of the Jezzine coast, Ain el-Helweh and Miyeh wa Miyeh, are practically juxtaposed and incorporated within an urban continuum. UNRWA estimates the number of Palestinian nationals living in Saida to be around 90,000, with two-thirds based in the camps and a quarter in the medina3 (old city). Most of the Palestinian refugee population in Saida came from Upper Galilee (located 50 to 70 km South of Lebanon), and more specifically from outside the town of Safed (Ras al-Ahmar, Safsaf, and Taytaba for example).

The mixing of populations was accentuated in recent years due to the arrival of refugees4 fleeing from Syria. At the end of March 2015, and for the sole district (Caza) of Saida, the UNHCR evaluated the number of Syrian refugees to be 50,147, of which there were more than 11,250 families. The refugees in Saida make up 4.3% of the refugees officially registered with UNHCR services.5 It is also worth nothing that this agglomeration has assimilated other forms of populations, mainly Shiite from the South, but also Christian from the Chouf region, some of which are permanently settled in Saida and its immediate surroundings.

Methodology

This brief report is based on a socioeconomic qualitative assessment and a conflict analysis, based primarily on political and historical analysis, as well as individual experiences and perspectives of key informants. The fieldwork was carried out in Saida and Beirut, between February 18 and March 31, 2015, with around thirty actors and respondents. Another round of fieldwork was undertaken in early May 2015, mainly to cross-check and triangulate data. This qualitative research included about 25 one-to-one in-depth interviews with religious and intellectual figures, NGO representatives, members or former members of the local authorities, and finally local residents, both Lebanese and refugees.

All respondents’ names have been anonymised to ensure protection of research participants.

The finalization process of this report has included the input of local experts as well as UN officials during the months of April and May 2015.

A complex social fabric

Local diversity is noted within the religious composition of Saida: nowadays, two-thirds of the populations residing in the city are Sunni, nearly 30% Shiite, and about 5% Christian (Greek-Catholic and Maronite in nearly equal proportions).6

The Sunni community is the largest, but also the most fragmented. In practice, the Mufti controls only a few mosques in his community and the resident Imams have autonomy over preaching, based on ideological affinity or depending on political connections.7

The Shiite community is also politically divided, although it seems much more organised than its Sunni counterpart, as it rallies around a limited number of powerful allegiances. Primarily, these allegiances are focused around two poles originating from the civil war militia order: the Amal movement and Hezbollah. Secondarily, they are organised around a few families of local traditional notability (Assad and Osseiran) linked to the two main Shiite parties through shifting relationships of dependency and concurrency, and for some, affiliation.

This diversity is further reinforced by a varied political constitution. In 1985, after the withdrawal of the Israeli army from the city of Saida, followed by the withdrawal of the Lebanese Forces from its Eastern suburbs, the traditional notables had to cope with the emergence of new political actors from the battlefield: Amal, Hezbollah, al-Jama’a al-Islamiyya, and Rafic Hariri.8 Since then, the political sphere has evolved on those bases, depending on fluctuating local and national interests and alliances.

A society struggling with increasing poverty

Despite being the administrative centre of a governorate (Muhafaza) and district (Caza), Saida has suffered economically early on from the proximity of the capital city. Throughout the past century, this has led to the continuous relocation of Sidonian families to Beirut, mostly drawn to its economic opportunities, its dynamism, modern port infrastructures, and advantageous customs taxes.9 Nowadays, except in the agro-food sector, Saida cannot claim to host any significant industrial or economic development. The manufacturing output is still mainly artisanal, and is economically poorly competitive.10 Hence, the city is above all a marketplace and a sub-regional administrative centre employing a significant number of civil servants.11 Even the fishing sector has not managed to prosper; it remains low-paying, and has suffered in recent years from the numerous pollution sources concentrated on the coast.12

“Despite being the administrative centre of a governorate (Muhafaza) and district (Caza), Saida has suffered economically early on from the proximity of the capital city.”

In reality, the only sector appearing to be slightly dynamic is the construction and public works sector. However, in terms of human development, this dynamism is an illusion. Like the national economic mechanisms in this sector, construction activities generate a great deal of external effects,

with mostly quite unfavourable consequences.13 These adverse externalities are a challenge to sustainable development, and place a great burden on the whole population. The use of land for real estate development seems to be suffering from a lack of binding legislation and a lack of strategic vision from the local and supervisory authorities, at least in terms of planning and development. Such practices are giving room for property speculation and rentier practices, thus concentrating the financial benefits in the hands of the building contractors and the landowners. Such facts would not be problematic if urbanism, town planning, and the overall quality of life that result from it benefited the whole local population. Real estate developers monopolising urban development, and the subsequent prevalence of commercial and economic profit logics, hinder the construction of affordable housing and neighbourhoods for vulnerable communities.

However, considering only transport or health matters, the impact of this ill-thought-out, non-selective property production causes considerable social costs, like for example the impact of high levels of pollution on the quality of life. Their adverse consequences have the most severe impact on the most vulnerable populations. This lack of strategic and col

lective vision is undoubtedly one of the key factors behind the dynamics of poverty in Lebanon in general, and more specifically in some medium-sized cities such as Saida.

Indeed, since the end of the civil war 25 years ago, poverty has become more prevalent,14 especially in recent years, owing to the influx of new refugees from Syria.15

“considering only transport or health matters, the impact of this ill-thoughtout, non-selective property production causes considerable social costs, like for example the impact of high levels of pollution on the quality of life. Their adverse consequences have the most severe impact on the most vulnerable populations. This lack of strategic and collective vision is undoubtedly one of the key factors behind the dynamics of poverty in Lebanon in general, and more specifically in some medium-sized cities such as Saida.”

The presence of poverty pockets, such as refugee camps, and the inherent socioeconomic difficulties therein have all contributed to generating a whole range of charitable and humanitarian associative activities. For some actors interviewed, a wide array of charitable organisations is active in Saida and taking advantage of the “crisis”, thus contributing to the development of a full-fledged parallel economy. Many charitable or development organisations have been created or seen a rise in their activities and funding following the influx of Syrian refugees in Saida. The ensuing injection of money is, on the one hand, contributing to inflationary trends, while on the other setting in place networks of clientelism, nepotism, and corruption within humanitarian work. This has resulted in in conflictual dynamics, as has been stressed during the fieldwork interviews by some interlocutors. Fieldwork accounts relay that this parallel economy and activities have become so lucrative that it seems somewhat incongruous to these stakeholders to wish for the advent of a development and welfare level of the populations that would make their presence unnecessary. Moreover, many respondents have expressed frustrations with the way local and international organisations have been operating, mainly disregarding needs of beneficiary communities, while others have highlighted the lack of transparency of some actors. Although these concerns have been predominant during the fieldwork phase, this brief report can’t explore this thematic in depth, as it needs a specific and more extensive investigation.

A fragmented public space

In the following section, we will first describe a very brief panorama of the evolution of the local political field, and then present a few of the main actors who currently carry a significant weight there. Finally, we will limit ourselves to pointing out the existence of other actors through a cartography (see map below).16

Lebanon’s weak institutional structures have limited capacity to fulfill their purpose, mainly due to the traditional existence of political favouritism. Simultaneously and dialectically, they contribute to the strengthening of those practices. At the society level, these sociopolitical practices are a source of division into client groups seeking protection and security from a leader, “Za’im.”

From the reconfiguration of the local notability...

In the decade following Lebanon’s independence, the traditional order in Saida was based on—and reflected—the prominent local notable families (Bizri, Jawhari, and Solh, among others).17 This order has remained in place, despite some adjustments.18 Internal developments within the local family oligarchic system have only resulted in reproducing the system itself.

However, as of the mid-1950s, this political system/functioning was progressively contested by the convergence of uprooted populations (mainly Palestinian refugees) within a nationalist-, socialist-, or populist-oriented ideological substrata. These emerging dynamics challenged the coherence of traditional patronage systems, and contributed to their reorganisation. The most innovative aspect of this new patronage system lies in the ideology- leader-party combination.

The parliamentary election of Maarouf Saad in 1957, and its subsequent conquest of the municipality in 1963, embodied this phenomenon. Indeed, by combining elements of both the Nasserite ideology and the Palestinian resistance, Saad managed to rally a large audience among marginalised communities in the city, mobilising them through the new Nasserite Popular Organisation (OPN), which he created in 1973 and ran until his death on 6 March, 1975.19 His eldest son, Mustafa, then took over until his own death, developing his leadership through a militia and a whole package of social welfare services (school, dispensary, direct grants, and allowances) and associations, thanks to subsidies granted to his party by mainly Palestinian organisations.20 However, behind the apparent progressiveness of the collective claims supported by a partisan militant base, the logic of patronage and political inheritance (wiratha siyasiyya) did not fade. In fact, Mustafa’s younger brother, Oussama, succeeded him as the leader of the party in July 2002, and still leads it today.

For the OPN, political syncretism, the struggles for the restitution of Palestine, Palestinian refugees’ compensation and right of return,21 and Arab unity ideology, were all issues that prevailed over other political considerations,22 leading the organisation to maintain a close relationship with numerous Palestinian groups, different left-wing actors (the Communist Party, community associations, and trade unions), and Hezbollah. It should come as no surprise then, that in the years 2012 and 2013, OPN supporters were publicly opposed to Ahmad al-Assir’s23 supporters on the basis of targeting Hezbollah over its involvement in Syria (more details on al-Assir and this conflict later in the report).

...to the domination of the local political scene by a single actor

Predominantly a Sunni city, Saida is also the birthplace of former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, assassinated on February 14th, 2005. It is not possible to understand Saida’s current makeup without taking a close look at Rafic Hariri’s work and practices.

Rafic Hariri’s charitable work began in 1979 with the creation of the Islamic Foundation for Culture and Higher Education (precursor of the Hariri Foundation, officially established in 1983). Through this first structure, he purchased around one hundred hectares in the village of Kfar-Falous, located halfway between Saida and Jezzine.24 On these lands, and until 1985,25 he undertook the development of a large multi-services complex (education, medical, social, and sports services),26 which was built by the Lebanese subsidiary27 of his construction and public works company. Developing patronage activities through his foundation, Rafic Hariri simultaneously continued to provide financial and material support to individuals. This patronage model, which created an unbalanced relationship—personalised, restrictive, and sometimes paternalistic—based on the consent of a service offer, was crucial for setting up a network of influence. It then established its control as a strong patronage network over the city of Saida. Hariri’s discreet sponsorship started to bear its fruits after the end of the Lebanese civil war, as he began making his way into a political field jealously controlled by the actors of war. The destruction of Saida28 in June 1982 and the three-year-long Israeli occupation that followed led Hariri to mobilise his financial strength29 to rebuild the city once more, consecrating him as an essential actor, despite traditional actors’ attempts to contain his emerging sphere of influence.

“This patronage model, which created an unbalanced relationship—personalised, restrictive, and sometimes paternalistic—based on the consent of a service offer, was crucial for setting up a network of influence.”

In order to achieve the creation of a real political base allowing him to dominate the political sphere, Hariri operated through three channels simultaneously. First, he sponsored a certain number of small local notables and elites. Second, he exerted his influence little by little on numerous public or charitable administrations30 thanks to the influence he had on their leaders and the appointments he managed to make.31 Finally, securing a political alliance with Nazih Bizri (representative of notable Sidoninan family) granted him access to Bizri’s middle-class powerbase (wealthy families, liberal professions, traders, and business men).

In the search of institutional legitimacy, Hariri chose to promote the candidacy of his sister Bahia Hariri during the first post-war parliamentary elections held in 1992. Bahia had already represented him locally, being the president of his foundation and a key member of his political entourage. Her candidacy allowed Hariri to avoid direct confrontation with Mustafa Saad, in order not to appear as a divisive figure in the city, and preserve his national aspirations.

Rafic Hariri’s political career was henceforth better known, and took shape in both Beirut and on the national scale, beginning with his appointment to Presidency of the Council of Ministers on 22 November, 1992. Still, up until his assassination and despite the progressive reduction of his patronage, Saida remained a Hariri stronghold. The city’s urban and social landscapes owe a great deal to the achievements he promoted. Moreover, the political configurations prevailing in Saida are largely conditioned by a scheme he significantly contributed to renew.

The post-2005 era and its impact on the local scene

Since the death of Rafic Hariri, the Hariri family seems to be subject to various conflicts of interests, one of the main ones being the control of the Hariri Foundation and its resources,32 both material and symbolic as per fieldwork accounts. These internal conflicts seem to have benefited Fouad Siniora’s33 personal political and social ambitions.34

At the local level, this political configuration determined by Hariri’s legacy in Saida consisted of some kind of alternation in the municipal majority, depending on conjunctural alliances. The candidature lists supported by the Hariri clan won the elections in 1998 (Future Movement) and 201035 (March 14 Coalition), while a Saad-Bizri political coalition, backed by Hezbollah and by a vast majority of the local Shiite community more generally, won in 2004. The municipal elections are combined with the election of the makhatir.36 There are 23 of them in Saida, over three land districts and 15 moukhtariyat:37 medina (13), Dekerman (1), Wastani (1). In addition to their administrative function for the management of the civil registers, they can play a key role during elections (mafatih intikhabiyah). It should be noted that, election after election, the inter-partisan tensions have grown crescendo: both media38 and local actors have reported an increasing number of violent confrontations.

At the level of the Caza, the municipalities nearby are electorally predominantly Christian or Shiite. Politically, they are currently dominated by Hezbollah, the Amal Movement, or the Free Patriotic Movement, all of which operate using patronage activities.

To summarize, this synthetic presentation of the main political actors in Saida highlights the existence of political dynamics, whose effects contribute to divide the populations more than they bring them together. In this regard, despite the efforts of many actors within civil society, and even political actors themselves, the general atmosphere prevailing locally since the Taif Agreement has not substantially contributed to the emergence of a pacified and democratic public space able to promote and increase the welfare of the populations.

The refugee populations and the camps

Beyond the humanitarian issues raised by their presence and their influx, the existence of refugees raises the question of their integration, at least into the local socioeconomic fabric. The instrumentalisation of the Palestinian refugees’ permanent settlement (tawtin) on the one hand, and of their “right of return” (al-‘awdat) to their homeland Palestine on the other, have both contributed to maintaining these populations in a status quo of marginalisation and precariousness.

Fieldwork in Palestinian camps and gatherings in Saida shows an increasing rupture between Palestinian youth interviewed and their traditional political representatives, namely the factions. The latter, along with their Lebanese counterparts, are perceived as a contributing factor to their marginal and precarious situation.

Far from constituting today the stronghold of Palestinian activism, the camps in Saida, and more generally in Lebanon, are pockets of poverty beyond the control of the central Lebanese state. As fieldwork accounts inside and outside Saida’s refugee camps show, camps are less perceived as threats in terms of security rather than in terms of increased social and economic marginalisation. Largely demilitarised and marginalised, Palestinians continue however to be perceived as a threat by the Lebanese population, in a context historically charged by the weight of the civil war starting 1975, and of the camps war in the 1980s.

While historically under Fatah control, the 1982 Israeli invasion has changed the situation in Saida as most PLO factions withdrew to West Beirut and its southern suburbs. The defense of the camp was mainly ensured by young radical Islamist militants. Thus, from the mid-1980s, the traditional authorities in Ain el-Helweh camp were increasingly challenged on an internal level.

These historical dynamics have consecrated Ain el-Helweh as a specific “space of exception,”39 which contributes to reinforcing the perception of the camp as a bastion of dormant or active jihadist cells. However, most respondents from the camp distance themselves from such groups, especially with the events of Nahr el-Bared and Aabra still fresh in the collective memory.

In the context of this short report, it is not easy to exhaustively present and analyse all the prevailing political and religious dynamics at play in the Palestinian camps of Saida. The situation became more complex since the arrival of nearly 6,000 Palestinians from Syria. Some fieldwork accounts have expressed concerns regarding so called “radical” groups inscribed in the conflict in Syria that may be located in the camp, and a systematic mapping of reported incidents (cf the Conflict Map and Graph below) shows relative heightened tensions in area. However, these incidents seem to be somehow played down in the discourses of local actors, especially since a majority of the reported and mapped incidents are classified as “individual acts of violence.”

In this charged context, both the Palestinian Liaison Committee and the camp’s security committee in charge of the major checkpoints have reinforced their cooperation with the Lebanese military authorities to avoid a “new Nahr el-Bared.”40

In this vein, it is necessary to address the issue of the future of Syrian refugees.

Indeed, the arrival of Syrian refugees to Saida is depicted by local actors as a challenge, especially in areas of the medina (hosting nearly 15,000 registered refugees) and the coastal villages of the Southern outskirts (the number of refugees in Bissariyeh, Ghaziyeh, and Sarafand is estimated at 3,500-5,200 refugees). Localities of the Eastern suburbs (Aabra, Haret, and Myeh wa Myeh) also host thousands of refugees.

In concrete terms, for the local authorities interviewed, the influx of Syrian refugees seems to be primarily an issue of both health and security, equally affecting the economic situation. In terms of security, several representatives have mentioned the fact that local populations have a negative view of the arrival of so many refugees, accused by some of generating an increase in petty crime.41

In terms of health and safety, there is a dense presence of refugees, especially in the coastal areas of South Saida, living in precarious and poor hygiene conditions with poor water drainage and sewage networks in the informal tented settlements. This can put local population at risk, but can also jeopardize the agricultural production,42 which is an essential constituent of the local economy.

There is no doubt that the arrival of professionally skilled Syrian refugees (tailors, carpenters, and young graduates, to name a few) put the job market under pressure and can lead to lower salaries, thus putting greater strain on the local economy and exacerbating tensions between host communities and refugees, as was observed during fieldwork. Over time, and with degraded living conditions, it seems necessary to campaign against openly stated and simplistic talk accusing the refugee populations of “stealing jobs.” While the above graph highlights increased tensions in the Ain el-Helweh camps, there are very few reported and mapped incidents involving Syrian refugees until the date of writing of the report.

“Social actors involved in Saida stressed on the importance of disseminating aid among impoverished local populations (Palestinian, Syrians, and Lebanese)”

Finally, while the education of refugee children is proving to be a challenge for humanitarian and development actors, some—mostly public—schools have enrolled some Syrian children. Additionally, a few initiatives by citizens and mobilisations seem to be developing in order to provide education and schooling for the refugee population. Some of the latter are even trying to set themselves up as associations so as to facilitate their efforts.43

The influx of aid and assistance targeting Syrian refugees is perceived by other vulnerable communities in the Saida area as happening “at their expense.” Some Palestinian refugees, for instance, have expressed their frustration at the perceived decrease of aid targeting camps and gatherings. This may constitute a factor in building tensions within poverty pockets.

Social actors involved in Saida stressed on the importance of disseminating aid among impoverished local populations (Palestinian, Syrians, and Lebanese), which will favour stabilisation and a better quality of life for everyone, while advocating for the recognition of the social and economic rights of refugee populations on the medium and long term.

The influx of Palestinian refugees coming from Syria to camps and gatherings is putting a strain on Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, thus contributing to increased tensions within Palestinian communities. Interviews conducted in Saida’s camps and gatherings emphasized heightened tensions that respondents are linking to “cultural differences”, as Palestinians from Syria have historically enjoyed better living conditions than their counterparts in Lebanon.

The struggle for space and spaces

If there are risks of social or community conflicts, potentially accentuated by the very strong increase of refugee populations in the past three years, it is important to address the issue of land and space (like mere access to public space). These issues hold interests and stakes that carry underlying risks. Therefore, we would like to draw the attention of the actors to the following rarely discussed points that are of concern to a number of individuals, groups, or actors.

In some parts of the city, streets and public spaces are subject to numerous appropriations, which may lead to conflicts between residents, shopkeepers, street or sidewalk vendors, and even beggars. Also observed in the field is the appropriation of spaces for parking, over-flowing in traffic areas, which generates difficulties, particularly in terms of cost of transport times. This reflects the issue of contested territory, i.e. a space that is “claimed”, whether “acquired” or “grabbed”, or a space that is subjected to planning for specific purposes.

Figure 5: The union of Saida-Zahrani municipalities includes 16 towns. It has had no president and vice-president since the municipal elections in May 2010. Coalition lists of the 8 March Movement (CPL-Hezbollah-Amal-families) won in most of those municipalities, while the list supported by the Future Movement and pro-14 March won in the Saida municipality. On another level, the influx and concentration of refugees in some areas pose significant risks on the environment. The backfilling and re-parceling operations are highly attractive for the developers, who are more concerned about speculative logics than about urban sustainable development.

On a different scale, Saida seems to be roughly divided between a “periphery,” which is politically in favour of the 8 March Movement, and Saida’s centre with the city’s municipal majority supported by the 14 March Coalition. Since June 2010, this bipolarisation paralyses the Federation of Municipalities of Saida-Zahrani: the elected officials have so far not been able to agree on a president. This invites us to revisit the conflict between Sheikh Ahmad al-Assir and Hezbollah, and then with the Lebanese army, on 23-24 June 2013.

At the mention of Ahmad al-Assir’s name, all the people encountered during fieldwork have confirmed their desire to turn the page of an event that they regard as non-representative of the context in Saida. Most of the actors interviewed mention that that conflict involved national as well as transnational political considerations that they regard as foreign to the city, and which should not, according to them, influence the city’s context. However, some representatives do not deny the political influence that Assir may have had on his coreligionists in his preaching, and regret political and media manipulations of this micro-phenomenon.

“the tactics adopted by the Lebanese Army during the “Assir incidents” are very different from those adopted in 2007”

In reality, if the Assir phenomenon has managed to spread so much in the years 2011-2013, it is also because it represented for the Future Movement an opposition force to the March 8 Movement (primarily Hezbollah) in a municipality of Saida’s suburbs— Aabra— favourable to the March 8 Movement. This support led to the dividing of the local populations along dual lines imposed by national political considerations, which are not considered Saida’s local political priorities and challenges, like increasing poverty and the need for a sustainable economic development. When al-Assir and his supporters took up arms against the Lebanese Army, it lead to an official rupture with the Future Movement.

It is interesting here to highlight how such clashes between the Lebanese army and armed groups reflect a general tendency to militarise conflict resolution processes. Such an approach was seen during the war on Nahr el-Bared and was widely criticised among human rights defenders in Lebanon.44

In contrast, the tactics adopted by the Lebanese Army during the “Assir incidents” are very different from those adopted in 2007. Targets were localised and delimited. The army’s actions were also portrayed as defense against militia-like groups, rather than attacks on a given civilian area, thus reflecting a strategic and operational shift by the Lebanese Army.

Another perspective is to consider space as object of ownership, which can provide a capital and/or an income. Real estate actors and private developers follow logics of profit generation, in context where real estate economy is a significant industry. They are thus are failing to accommodate marginalised and vulnerable communities notably in terms of access to housing, economic participation, or basic services. In addition, there are the exorbitant social costs (transportation, pollution, health, etc.) generated above all else by the virtual lack of strategic planning, minimal urban planning, and building regulations and practices favouring immediate economic capital gain. These costs are borne by the most marginalised and vulenrable populations.

Saida exemplifies noninclusive urbanization and development projects. Apart from the private real estate development activities, there were no less than 47 urban projects for the sole municipal territory of Saida in 2013. These projects represented a global investment amount of nearly $500 million, which is 100 times the municipal budget. Conversely, the municipality and town people were only consulted for two projects, representing 4% of the investment amount.45 In these conditions, there is still a long way to go to set up participatory procedures that would encourage citizens to get involved according to a bottom-up process.46

Since 2011, through its participation in the Medcities network,47 the municipality has engaged in the development of an Urban Sustainable Development Strategy (USUDS). This strategy can be considered as a first step for informing and reinforcing local institutions, especially municipal, in regard to strategic planning in the city. However, the process seems to encounter challenges, such as land re-parceling or construction density.48

It is worth noting that there are similarities between Saida and Tripoli: land re-parceling, coastal embankment, development of a sewage disposal system flowing into the sea, heritage presentation program of the medina,49 etc.

Based on interviews with local activists, for instance, some major projects carried out to address issues such as Saida’s landfill site, raised concerns about the promotion of sustainable practices, specifically regarding possible privatisation of public spaces for speculative property development purposes.

Among the above examples, the re-parceling of the East Wastani area in Saida seems to mostly accommodate the interests of some particularly powerful political and economic actors. Currently “on hold” according to interlocutors due to numerous complaints from former owners having been “cheated,” the re-parceling operation also raises concerns amongst Palestinians, even in Ain el-Helweh camp. The interlocutors seem to say that some of the re-parceling stakeholders may find advantageous the possibility of a small group causing a similar situation to what happened in Nahr el-Bared, especially as this would also entail extending the re-parceling to the Dekerman South area located between the Palestinian camp and the sea. However, unlike the case of Nahr el-Bared, the opportunity would be seized to install the camp in more remote outskirts and to reclaim lands with high financial and real estate potential. Without anticipating the possibility of such a scenario happening or not, it is noteworthy that this issue worries a significant number of actors interviewed.

Conclusion

This report seeks to provide an elaborate and complex description of the different social, political, economic, and spatial conflicts in Saida. It relies on a structural and historical analysis to address the political and socio-economic fabric of the city, the relations between refugee populations and locals, and their emerging needs and concerns regarding current and future conflicts. Based on fieldwork research, this report provides analysis and descrip- tion of the current situation in Saida, drawing from several perspectives on the issues of changing political allegiances, policies of healthcare, and development and property, land and space, all seemingly influencing, affecting, and producing conflict.

This closer look at Saida leads us to make the following recommendations as concluding remarks.

Recommendations for action

- At the local associative level:

- Local organisations should advocate for a more rights-based and holistic policy to manage the Syrian refugee crisis, and lobby with political actors to avoid the scapegoating of refugees in the context of structural issues and inequalities preceding the crisis.

- Support should be provided to emerging local Palestinian and Syrian groups and collectives to organise autonomously, and training should be provided to report human rights violations.

- Aid should be delivered to poverty pockets, and specifically to Palestinian camps and gatherings, while at the same time not overlooking advocating for long term rights.

- Local organisations, whether charitable or working on long term development, should abide by transparent processes of action, which hold them accountable to beneficiaries and not only donors. International NGOs should also abide by accountability processes specifically respecting beneficiaries’ needs, and enhance their collaboration with local organisations. All non-governmental organisations operating in Saida should abide by inclusive and participatory processes (taking into account beneficiaries as well as other stakeholders) in planning responses and development initiatives.

- At the local authority level:

- Local authorities, notables, and the main political parties in Saida should favour and enhance non-militarised conflict resolution dynamics and processes.

- Local authorities, in collaboration with authorities on the national level, should urgently address the issue of public space, which tends to be used, to a large extent, to the detriment of public interest and, as this report shows, is directly linked to the eruption of conflict. The sustainable development of Saida requires inclusive processes and the reinforcement of public policies and tools in terms of property, as the struggle for spaces in the context of increased poverty is creating heightened tensions and conflicts.

- Local authorities and the private sector in Saida should focus on the development of income-generating activities so as to reduce the risk of conflicts linked to job competition. Other priorities should prevail over real estate development business which is becoming an end in itself. This is a particularly difficult challenge as the affordable housing crisis affecting the whole country preceded the arrival of the Syrian refugees.50 Their arrival merely reinforces this phenomenon, which primarily benefits property specula- tors and slum landlords, but is in contradiction with the principles of sustainable economic development.