For the first time in nine years the Lebanese political scene is mobilising for elections. Although little has changed in the overall makeup of Parliament, the 2018 parliamentary elections exhibit significant differences, with a record 976 registered candidates, 113 of whom are female. A number of both male and female registered candidates, came from outside traditional establishment parties and zu‘ama which have historically dominated Lebanese politics. This briefing paper looks at the emergence of “new” political groups by tracing the trajectories of their politicisation and political engagement, and contemplating their accumulated experiences, notably in civil society circles. Exploring their discourses and programmes, the main recurring thematics revolve around the secularisation of the state, the rule of law, human rights, and equal provision of basic services. It is also noteworthy that they share similar views on economic reforms, and the reinforcement social safety nets. Despite these similar positions, creating electoral lists has proven to be challenging, leading to the withdrawal of many candidates.

This briefing paper is available in English and Arabic, and is published in the frame of the call: "New on The Scene, Can Emerging Political Actors and Women Make Headway in Lebanon's 2018 Parliamentary Elections?".

For a thorough discussion of women's participation in Lebanon's 2018 Parliamentary elections, see: Catherine Batruni & Marcus Hallinan, "Politics, Progress, and Parliament in 2018: Can Lebanese Women Make Headway?".

SUMMARY OF KEY FINDINGS1

For the first time in nine years2 the Lebanese political scene is mobilising for elections. Although little has changed in the overall makeup of Parliament, the 2018 parliamentary elections exhibit significant differences, with a record 976 registered candidates, 113 of whom are female.3 A number of both male and female registered candidates, came from outside traditional establishment parties and zu‘ama which have historically dominated Lebanese politics. This briefing paper looks at the emergence of “new” political groups by tracing the trajectories of their politicisation and political engagement, and contemplating their accumulated experiences, notably in civil society circles. Exploring their discourses and programmes, the main recurring thematics revolve around the secularisation of the state, the rule of law, human rights, and equal provision of basic services. It is also noteworthy that they share similar views on economic reforms, and the reinforcement social safety nets. Despite these similar positions, creating electoral lists has proven to be challenging, leading to the withdrawal of many candidates.

“Civil society”: a new political actor?

Civil society can in broad terms encompass everything that is neither military nor religious, including political parties and a variety of non-state actors. It was defined by French diplomat Alexis de Tocqueville as the “voluntary, non-political social organisations that strengthen democracy preventing a tyranny of the majority.”4 According to de Tocqueville, “these associations protect diversity and prevent the fragmentation of society by forcing men to consider the affairs of others and to work with their neighbors.”5 There is a widespread preconception depicting civil society in Lebanon as “one of the most vibrant civil societies in the Arab world.”6 However, this notion is often under-researched and various types of organisations and/or movements remain unaccounted for.

In Lebanon the term “civil society” is currently widely used – particularly by Lebanese and Arab media in their reporting of Lebanese election-related news – to refer to candidates from outside the mainstream political arena.7 The use of this term also reflects the vertical polarisation between mainstream political parties often perceived as corrupt and sectarian; and those against them, i.e. “new” alternative forces, referred to as “civil society” as a generic term. These “civil society” groups are currently depicted as the “other,” with more integrity than the existing political elite – who have consolidated their wartime militia rule but have failed during the so-called “cold civil peace,” to recover from wartime practices due to limitations in the political system, sectarian-based constituencies, and malpractice in postwar governance.8

However, those commonly referred to as “civil society” groups or candidates in the upcoming election race are rather emerging political actors. This briefing paper defines them as individual actors campaigning within newly established platforms or coalitions that did not take part in the previous electoral cycle of 2009. We define them as “new” based on three factors differentiating them from more traditional parties: i) they do not claim any kinship with family, sect or even region; ii) they adopt a rights-based discourse and are outside of the existing service-based clientelistic networks; and iii) their political engagement is intra-Lebanese, and they do not claim any affiliation to regional and/or international blocs. In this sense, their background, approaches to politics, and praxis are different.

It is noteworthy that the upcoming elections have also made way for the emergence of candidates who are unrelated to mainstream parties or leaders, yet cannot be considered part of civil society groups. In fact, many have previously engaged in service delivery and retain district-based discourses that call upon regional and often sectarian sub-identities. 77 lists were registered in the Ministry of Interior and Municipalities covering 597 candidates competing across 128 parliamentary seats.9 These seats were previously assigned to 11 sects across 26 districts but were recently re-arranged under electoral law 44/2017 into 15 electoral districts.

On 6 May 2018, 3,744,245 Lebanese individuals,10 both in Lebanon and abroad, are eligible to cast their ballots in this new system, and hence – in theory, at least – contribute to the formation of a political class for the next four years. In light of this, we discuss to what extent the current electoral law presents opportunities for “new” political actors to enter Parliament and whether this may mark a new era in Lebanese political life.

The genesis of emerging actors

In 2005, in the aftermath of former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri’s assassination, youth activist groups were actively involved in the so-called Cedar Revolution. This was particularly in the form of underground university clubs, as independent individuals or as partisans of outlawed Christian parties. Among these were also members of the “Communist Students” (tullāb shuyu’iyūn), a dissident group within the Lebanese Communist Party that later coalesced under the Democratic Left Movement,11 led mainly by Elias Atallah and Samir Kassir. Many of the active youth from 2005 are now candidates in the current elections.12 Between 2005 and 2015, these individuals gradually merged into a socio-political movement, attracting political and social activists from inside and outside mainstream parties and groups. This growing, yet amorphous movement has often enticed partisans to desert their own parties in favour of new platforms, even if they are yet to be clearly defined. When asked about reasons for leaving their parties, all seven former partisans interviewed for the purpose of this research stated an absence of democratic practices inside party structures as well as dissonance between principles and practices, or “what we say and what we do”13 in the words of Assaad Thebian, candidate for a Druze seat in the Beirut II electoral district.

In 2015, thousands of people demonstrated in Beirut and other regions across Lebanon, to protest against the government’s failure to effectively respond to the solid waste management crisis, which resulted in tons of garbage piling up in streets across Beirut and its suburbs. While this event was a milestone in the contemporary history of civil movements in Lebanon,14 it was not a mere sudden awakening of apolitical individuals who became exasperated by the garbage crisis. Rather, it ought to be analysed as a part of a longer temporality of political activism that started before 2005, and is entwined with early waves of dissent against the 30 year Syrian occupation of Lebanon. Student groups were active as early as the late 1990s,15 with civil campaigns such as Baladi Baldati Baladiyyati in 1997-1998. This was the first of its kind after the end of the civil war and pushed for municipal elections to be held on time, activist Paul Ashkar explained.16

Between 2005 and 2018, eight notable phases (Graph 1) can be identified as milestones driving the emergence of new political actors who mostly became visible only in the current race for Parliament.17

Over a 13-year period, civil society movements in Lebanon have rallied around mostly thematic causes and issues that often came about as reactions to certain events or government shortcomings such as failures to address urgent issues or maintain legality and constitutional practices.

The politicisation of civil society groups

In the 2018 parliamentary elections, 66 candidates have emerged from civil society groups and affiliated individuals. They have formed lists in nine out of 15 electoral districts under the Watani Coalition. There are also other lists claiming civil society backgrounds in several districts, as well as numerous former civil society activists who have joined mainstream party lists. From the 12 candidates interviewed in Table 1, only one candidate (Hani Fayad) was not part of any of the campaigns preceding 2015 (with the exception of the campaign for the downfall of the sectarian system). Fayad explains the foundation of Badna Nhāseb in 2015 as “a collective of so-called nationalist parties such as the Talī’a party, close to [the] Iraqi Baath, the People’s Movement of Najah Wakim, and the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP) – al-Intifada, as well as individual activists, mostly ex-members of the Lebanese Communist Party, to accompany street protests, and to serve as a more grassroots platform.”18 All others had previously taken part in civil society movements, but the majority had never really experienced partisan politics. Neamat Badreddine a former member of the Lebanese Communist Party and a founding member of Badna Nhāseb, has been active in civil society movements, especially for women rights and personal status law. She says “I am a political activist and I believe in the intersectionality of causes; they are civil in nature but can never be solved outside politics. In that sense, our struggle is deeply political.”19

Despite significant differences in the political backgrounds of the 12 candidates interviewed, the majority of them self-identified as coming from rather modest families, lower middle class to middle class in general, with a few belonging to the upper middle class. Assaad Thebian is the exception, saying “I experienced extreme poverty, and lived through hardship conditions.”20 None hail from wealthy or political families, nor have they benefited from familial economic or social capital. In this sense, candidates from emerging political groups are “ordinary people.” They are citizens who have struggled to find their place in Lebanese society beyond sectarian, clan, tribal, and militia-based lines, which have monopolised power structures in postwar Lebanese politics.

Of the 12 candidates interviewed, three had previously submitted their candidacy for parliamentary elections in 2013, before Parliament voted for a 17-month extension of their term, which canceled the scheduled elections. When asked whether their decision to run for elections in 2018 was mainly driven by the adoption of a new law with a proportional representation system, most candidates interviewed said they would have run for elections irrespective of the electoral law.

When asked about why they decided to run for the 2018 parliamentary elections, most candidates interviewed considered that they had a duty and an opportunity to be part of the institution in charge of forging laws. Gilbert Doumit, candidate for the Maronite seat in Beirut I district explains that “we should move from demanding change to supplying it.”21 In the words of the “For the Republic”22 movement, their candidacy is a way of taking their activism “from the street to the Parliament.” This means that activists want to take on the role of policy makers and advocate from inside the Parliament in favour of the causes they have championed as activists. Josephine Zgheib considers that “the upcoming elections are a natural continuation of the struggle that started in 2015.”23 Thus, the rallying point provided by the elections marks a major turning point in how these individuals approach politics, and a period of political maturation for civil society groups, where they have come to realise that politics is not only about protesting and contesting the government, but can also be a way to challenge the system from within.

Table 1: Previous and current political affiliations of interviewed candidates

|

Name of candidate |

Affiliation to mainstream political parties |

Affiliation to emerging political actors |

|

Rania Ghaith |

No previous partisan affiliation |

Watani Coalition (My Nation), (Li Haqqi (For My Right) list in Chouf-Aley) |

|

Gilbert Doumit |

National Bloc |

Watani Coalition (My Nation) (Li Baladi (For My Country) list in Beirut I and II) |

|

Nayla Geagea** |

No previous partisan affiliation |

(Li Baladi (For My Country) list in Beirut I and II) |

|

Mark Daou |

Democratic Left Movement |

Madaniyya (civil) list in Chouf-Aley |

|

Imad Bazzi** |

Democratic Left Movement |

Min Ajl al-Joumhouriyya (For the Republic) |

|

Vicky El-Khoury Zwein |

Pro-Aoun university groups National Liberal Party |

Sabaa Party (Seven) , Watani coalition list in Metn |

|

Neamat Badreddine |

Lebanese Communist Party |

Badna Nhāseb (We Want Accountability) Sawt al-Ness (Voice of people) list in Beirut II |

|

Hani Fayad* |

Syrian Social Nationalist Party – al-Intifada |

Badna Nhāseb (We Want Accountability) Sawt al-Ness (Voice of people) list in Beirut II |

|

Nada Ghorayeb Zaarour |

No previous partisan affiliation |

Green Party, Nabad al-Matn (pulse of Metn) Kataeb list in Metn |

|

Marwan Maalouf** |

No previous party affiliation / 14 March youth groups |

Min Ajl al-Joumhouriyya (For the Republic) |

|

Assaad Thebian** |

Union of Progressive Youth |

Tol’it rihetkoum (You Stink Movement) |

|

Josephine Zgheib |

No previous partisan affiliation |

Muwatinūn wa Muwatināt fi Dawla (Citizens in a State), Watani coalition list in Jbeil-Keserwan |

* Hani Fayad is the only activist/candidate who is still a member of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party – al-Intifada (SSNP), a branch of the mainstream SSNP that split in 1955, more known historically as SSNP – Abdel Massih, and currently under the leadership of Dr. Ali Haidar, minister of reconciliation in Syria. This branch of the SSNP is different from the SSNP that is more popular in Lebanon, as it refused to take part in the 1958 conflict and did not participate in the Lebanese civil war.

** These candidates could not join lists, hence dropped their candidatures as of 27 March 2018.

The discourse of emerging political actors

While emerging political actors come from diverse personal, professional, and political backgrounds, they appear to have had similar political trajectories, often in common activist circles, with shared political values and principles, translating into similar political and electoral programmes.

The 12 candidates interviewed were asked to list the top five political priorities currently addressed in their electoral programmes. Graph 2 below shows that the 12 candidates interviewed have similar views on priority issues, particularly around reinforcing social safety nets. Candidates also have very similar positions on economic reform issues, including economic development, growth, and job creation. Many candidates also mentioned the need to shift from a rentier to a productive economy. Environment was a priority for five out of 12 candidates, along with good governance principles and practices, and strengthening public institutions and the rule of law.

Graph 2 shows that the candidates’ programmes revolve around four main themes – secularisation of the state, rule of law, human rights, and equal provision of basic services – which correspond to issues advocated during their years engaged in civil society. Their convergence on reinforcing social safety nets and drastic economic reforms is related to their approach to policy making and their understanding of social change in Lebanon. As put by Nayla Geagea, “the entry point to any peaceful change in the Lebanese political system has to go through the dismantlement of the clientelistic networks of parties and leaders, and this can only be done if strong state institutions provide citizens with quality basic services.”24

Some observers have criticised the economic reform programmes of some new political actors25 citing a lack of overall re-examination of the economic system in Lebanon. However, interviews show that their economic proposals include significant measures, such as overhauling the fiscal system and tax policy to include higher taxes on capital and bank revenues, reviewing the servicing of public debt, increasing public investment in infrastructure and supporting productive sectors.26 Thus, the approach of emerging political actors is not based on performing better within the existing system, but is rather focused on a comprehensive re-thinking of Lebanese public policies, directed along three main principles: basic rights of citizens and protection of their interests, secularisation of the state, and enhancing the rule of law.

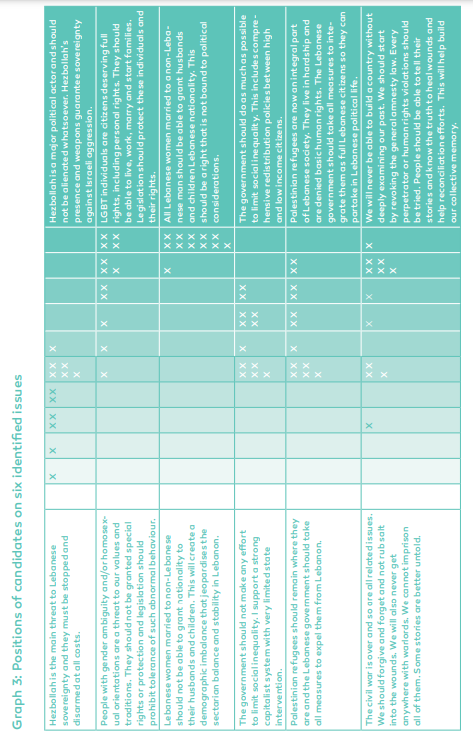

In addition to the previously identified thematic areas, interviewees were asked to determine their position on six other issues on a scale from 0 to 100, where 0 and 100 represent extreme positions at both ends, as shown in Graph 3. These topics were selected because they are controversial and could expose significant variances in the positions of emerging political actors.

These graphs, cross-analysed with the narratives garnered during interviews show that the 12 candidates appear to agree on most of the thematic issues, while overall adopting rights-based positions, in line with their backgrounds as human rights activists. For example, 11 out of 12 candidates fully supported the right of Lebanese women to grant their nationality to their non-Lebanese husbands and children, regardless of their initial nationality. Some of them explained that this has to be part of a general naturalisation policy, not only on ad-hoc basis, as is currently the case. All candidates also supported the rights of LGBT people to protection and dignity in line with their belief in human rights and personal freedoms. However, many of them were reticent when it came to granting LGBT individuals the right to marry and have families, because for them this is not yet a priority, and the struggle for rights ought to be gradual. A similar position was put forward by candidates regarding the issue of Palestinian refugees.

The question on Hezbollah appeared as the most controversial among these candidates, with a 50% difference between the lowest and highest scores in the position towards the weapons of Hezbollah (Vicky Zouein and Nayla Geagea respectively). Vicky Zouein considers Hezbollah to be a threat to Lebanese sovereignty but does not support forceful disarmament, while Nayla Geagea along with six other candidates consider Hezbollah a major political player that has protected Lebanon against Israeli occupation in recent years. All candidates agreed on the necessity of engaging in constructive long-term dialogue with Hezbollah, agreeing that the party’s weapons are not the main reason for the political and economic degradation of the country.

Finally, positions also diverged when the question of the civil war and collective memory was raised. Some candidates considered that this topic should only be raised to resolve the issue of the 17,000 forced disappearances, while many others considered that Lebanon should go through a fully-fledged transitional justice process.

Despite significant similarity of positions expressed by candidates, the list formation process has been strenuous. Between 7 and 27 March 2018, activists and candidates engaged in lengthy and sometimes heated discussions about lists and coalition building.27 This uneasy process resulted in many withdrawing their candidacies because joint lists could not be formed. This indicates a failure to tackle certain challenges, primarily ideological differences, competition between groups or individuals over the same seats, and vetoes imposed by certain activists on other candidates, particularly those from political backgrounds such as Ziad Abs and Paula Yaacoubian in Beirut I, and Ghada Eid in Chouf-Aley.

On a more positive note, this is the first time that women and men with civil society backgrounds and from non-mainstream parties, have succeeded in forming electoral lists across a majority of electoral districts. Although they expressed unease about running for seats assigned by sect, they have attempted to maneuver within these constraints, aiming to “reform the system from within.” Regardless of the election results, the emergence of this new generation of political activists represents a new era and form of political activism and practice in Lebanon.

The way forward for political renewal in Lebanon

From activism to political praxis

Based on the findings in this briefing paper, it is crucial for emerging political groups to take charge of their role as such and restrain from clinging to their civil society background as a way of dissociating from mainstream parties and leaders. In the short term, candidates need to be vocal about their new status as political actors. Over the long term, these groups should formalise and fully engage in Lebanese political life. This should go beyond being an amorphous crowd contesting government to becoming a pro-active and organised movement for setting the agenda and finding a voice in public debate.

Towards more critical and vocal actors and programmes

For the upcoming elections, civil groups should be also more vocal about their programmes and demands, and clearly formulate their positions and approaches to avoid confusion and misunderstanding. To better speak the language of citizens, these groups should resort to pre- and post-election qualitative public opinion research. Finally, emerging political groups should not fall into the trap of the consensus model of Lebanese politics, whereby everyone has to agree on everything. Civil groups should celebrate and build on where they converge and recognise and respect where they diverge.

Setting the pathway for further democratic reforms

On a national level, the new Parliament will need to rethink the electoral law in order to ensure a better representation of various groups and safeguard democratic principles of the electoral process, in terms of guaranteeing equal opportunities for candidates. This mainly applies to access to media and electoral spending limits. Reviewing updated legislation for political parties should also be a priority in order to restore trust in partisanship and normalise the Lebanese political sphere.